Food web schemas

Neo4j does not enforce constraints, it is possible to store information in any way possible. The Neo4j introduction to graph database concepts provides some details on how this happens. To facilitate straightforward methods to access information, it can be helpful to come up with a set of rules for how data should be stored. By storing data according to a set of rules, it becomes easier to define general Cypher queries that can access the appropriate data.

When deciding on how the data is stored, the result is usually a database schema. Schemas can be visualized as graphs, but they can also be described verbally as a set of rules or constraints. A database schema contains nodes (pieces of information) and relationships between these nodes. Nodes can have properties. For example, if we want to make a node that represents Pisaster, we could choose to have a node with the label Starfish, a Genus property that says Pisaster and a Species property that says ochraceus. However, for speed of access of databases it can matter a lot whether information is stored as a (node or relationship) label or as a separate node. This is because the Neo4j databasement management system (DBMS) uses graph traversal to return query results. Moreover, we should also keep in mind that Paine chose to keep his food web illustrations simple, so a single node represents an entire group of organisms.

If we were to define Pisaster as described above, a Cypher query to find all species belonging to the genus Pisaster would look like this:

MATCH (n:Organism {Genus: 'Pisaster'}) RETURN nThe DBMS needs to access the property Genus. For a simple query like this, the speed loss of accessing properties is not that large, but for complicated queries and larger databases, this can become important. Therefore, if we have a large enough database that we might have several species of Pisaster and need to query by genera, it makes sense to add a separate node with Genus label. The query to find all instances of Pisaster would then look more like this:

MATCH (n:Organism)--(:Genus {name: 'Pisaster'}) RETURN nIn addition to speed advantages, the Genus node only needs to exist once in the database and can then be connected to all other instances of Pisaster. Again, for small networks this is not a significant problem, but if we have a database with 100000 instances of the phylum Proteobacteria, we might start getting performance gains by storing Proteobacteria as a single separate node rather than a node property for each taxon, OTU or ASV.

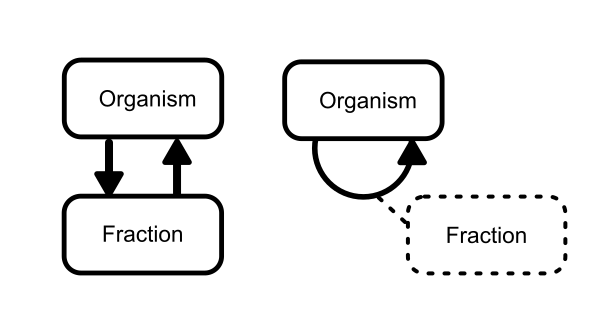

For this example, two different database schemas could make sense for the Pisaster subweb (Figure 2). We could also include each organism as a Predator or Prey node, but that would not make a lot of sense for Thais sp., since these organisms are both predator and prey. However, many other variations are possible, all of which contain the exact same information but may have consequences for query speed and query complexity. One schema is not necessarily better than the other; rather, it depends on the needs to use this information. The fraction can be considered both a separate node and a property of the predator-prey relationship. Both options are fine and neither is expected to affect performance of this subweb, since accessing relationship properties is unlikely to take a prohibitively long time. For this demo, we will use the schema with fractions as relationship properties, to address how these can be used to query a network.